What is vaccine misinformation?

20 Jul 2023

In November 2021, I was invited by Health Data Research UK (HDRUK) to give a talk as part of a public webinar on vaccine safety. One of the goals of this webinar was to allow members of the public to ask questions and interact with professionals carrying out research in this area.

The event seemed to me to be relatively successful. I presented results from a study I had recently carried out, the main finding of which was an association between vaccination with Oxford-AstraZeneca and elevated risk of cerebral venous sinus thrombosis (a type of blood clot in the brain). This was followed up by some thoughts and open questions about policy-making that were meant to prompt further discussion in the Q&A section. Videos of the presentations were uploaded on to HDRUK’s Youtube channel. I was happy with how everything went and hadn’t given a great deal of thought to it after that.

That changed recently when I learned that the video of my talk has been taken down from Youtube due to spreading medicial misinformation. That is rather a serious charge, which I intend to address here.

What was in your talk?

I don’t have video of the talk, though I do still have the slides. You can see them here.

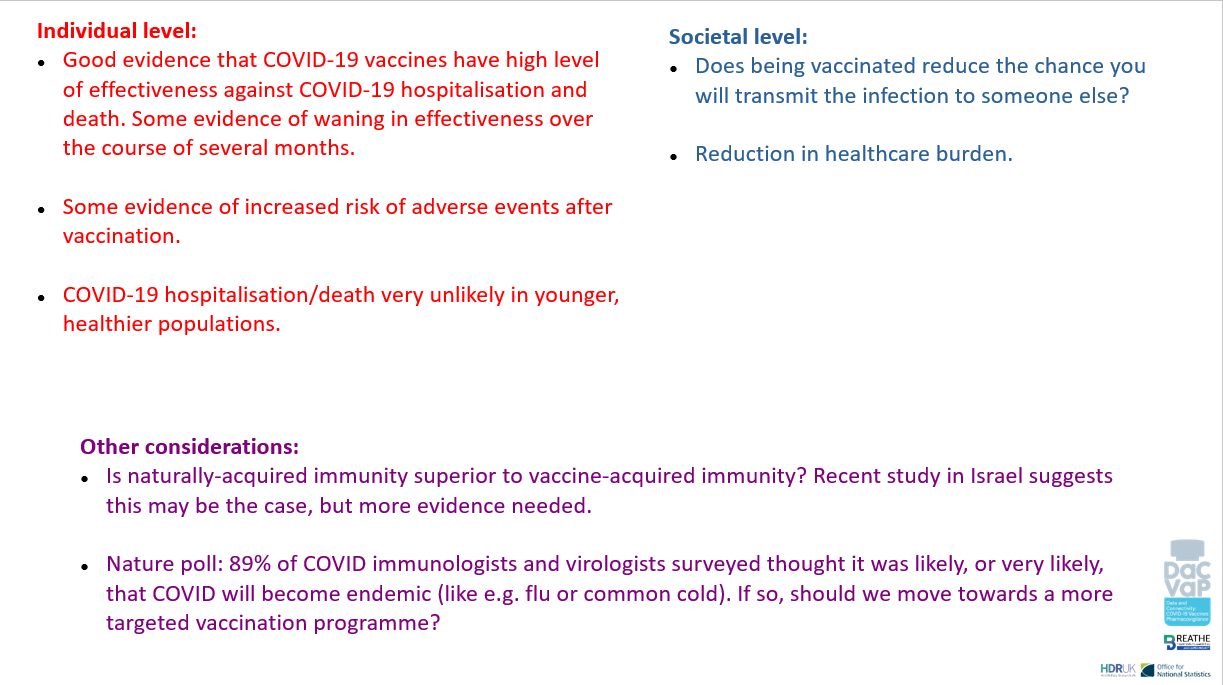

I don’t believe the part of the talk where I presented my research that has now been published in top peer-reviewed journals, could in any way be interpreted as medical misinformation. I therefore can only assume the offending content is on slides 13-15, where I discuss risks and benefits associated with vaccination, and possible policy-making implications. In particular my best guess at the culprit is the following slide:

Here again I consider more or less all of this content to be an uncontroversial precis of the state of our scientific knowledge; but perhaps it is the following bullet point that rankled:

Does being vaccinated reduce the chance you will transmit the infection to someone else?

Now this was, and still is, a perfectly valid question to ask. Vaccine effectiveness against transmission is an extraordinarily difficult topic to study, because transmission events are not well-recorded in the same way e.g. COVID-19 hospitalisations or deaths are - we do not have clinician-created records of when and why transmission events occur.

There are some also other very serious issues to contend with in studying vaccine effectiveness against transmission. One huge confounder is the fact that being vaccinated may cause people to behave in ways that increase their risk of contracting COVID-19. This was particularly the case at the time I gave the talk, because there were vaccine mandates in place that, for example, prohibited people from attending various public places if they were not vaccinated. Freedom of movement and association was essentially being offered up as an incentive by governments to get vaccinated.

Another big issue is the fact that vaccination may cause individuals to have much milder or even unnoticeable symptoms when they are infected, which in turn makes them less likely to engage in e.g. social-distancing practices.

This all means that there is not what I would consider strong scientific evidence on this question. By contrast, as far as effectiveness goes the evidence is rather unequivocal; there are a multitude of clinical trials as well as observational epidemiolgical studies that point to high levels of effectiveness against severe COVID-19 outcomes. This is simply not the case for transmission. And it was even more true at the time that the talk was given, when there were even fewer studies on effectiveness again transmision than there are now.

For these reasons, I considered this question to be completely fair-game, and one that had not been definitively answered in the scientific literature. I also considered it to be significant from the public health point of view to not encourage complacence on the part of people who were vaccinated, who might be less inclined to use masks, wash hands, observe social-distancing practices etc, as a result of a misplaced level of confidence in effectiveness against transmission not justified by the available evidence.

If that is medical misinformation, what else is?

If YouTube believes my talk constitutes medical misinformation, it is indicative of some very deep problems with their policies. They either believe that statements in accordance with a scientific consensus, or that honest raising of questions that have not definitively been answered in the scientific literature, constitute medical misinformation. Neither is a particularly good look.

Has our zeal to suppress conspiracy theories fuelled the fire of conspiracy theories?

Presumably part of YouTube’s motivation here is to suppres the spread of ‘conspiracy theories’. I have to say that I find the record of large social media companies on this front to be dismal and extremely worrying. As Joe Rogan has pointed out, there was a time when people were being suspended or banned from social media sites for spreading the ‘misinformation’ that you can still be infected with COVID-19 after receiving the vaccine. The idea that this is misinformation is now absolutely laughable, considering the huge proportion of people that have been vaccinated and subsequently contracted COVID-19.

The concern I have is that by vigorously suppressing discussion of completely legitimate questions the public had about vaccines, rather than quelling conspiracy theorists, social media companies may have emboldened and galvanised them. After all, if there is nothing to hide, then why did various authorities so fastidiously preoccupy themselves with curating what information the public can access and what questions they are allowed to discuss?