The trouble with economics

02 Oct 2024

In this post, I’m going to give an overview of some major theoretical issues in modern economics.

Supply and demand

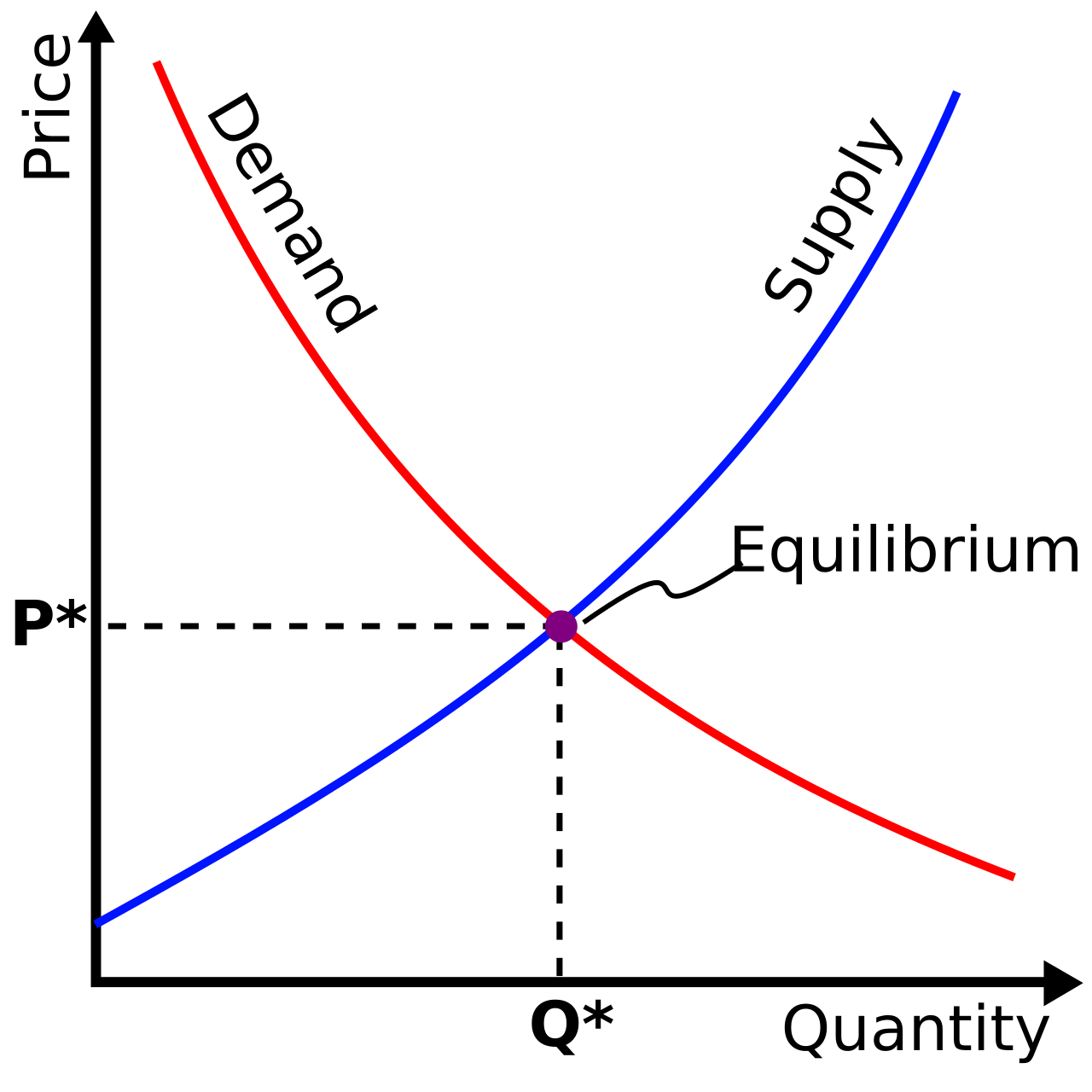

In a typical undergraduate economics degree, you spend a lot of time drawing pictures like this:

I don’t think its an exaggeration to say that a major chunk of the syllabus is pretending these diagrams are deeper and have far more explanatory power than they really do. It is, after all, just a graph with two lines.

The basic idea is that when prices go up, demand goes down and supply goes up. The two lines have to meet somewhere, and this is the price that clears the market. Under ‘normal’ circumstances, this is the price that actually prevails (or so the story goes).

General equilibrium theory

By the time you get round to doing a masters in economics, you learn the grown up version of supply and demand diagrams - it goes by the name general equilibrium theory. Here there are many goods that are traded concurrently. Each person has preferences and a budget. A major theoretical result in economics is the proof, under fairly general assumptions, that there is always at least one set of prices that clears the market.

General equilibrium theory is the theoretical foundation for modern macroeconomic modelling. Pretty much every mainstream macroeconomic model is either an example of a general equilibrium model, or it is derived from one. This includes models that are routinely used by major financial institutions like central and commercial banks, government treasuries etc for economic forecasting. For example, the ubiquitous ‘dynamic stochastic general equilibrium’ models.

The trouble with general equilibrium theory is that it has features baked in that are in spectacular disagreement with reality.

No money

In general equilibrium theory, there is no money. You might be puzzled by this - how can it be that the foundational macroeconomic modelling strategy of major financial institutions throughout the world does not have money? Is money not a central focus of the entire subject of economics?

Well yes, it is, but turns out it’s a lot easier to make models without it. First consider the useful role that money serves

- Medium of exchange

This is perhaps the primary and most important function of money - facilitating the exchange of goods. Without money, we would have a bartering economy in which a great deal of time and effort would be spent engaging in chains of trades that have the desired outcome. For example, if I have a cow and I would like to get a sack of potatoes, I would either have to find someone who has potatoes and wants a cow, or find a series of similar trades that eventually ends with my desired result.

- Store of value

Money provides a means through which you can e.g. provide labour now in exchange for consumption later. For example, you can go to work tilling the fields, get paid into your bank account, then later use that money to buy a four-slice toaster.

- Standard of deferred payment

This is closely related to the function of money as a store of value, but in reverse. That is, you can get consumption now in exchange for work later. This is achieved by borrowing money to fuel today's consumption, and paying back at a future date.

- Unit of account

Finally, money provides a measuring stick for value. If a good can be sold for £1, we have a numerical measure of its value relative to other goods.

Any model that includes money must capture all of these functions.

In general equilibrium theory, there is a set of market-clearing prices that certainly serve as a unit of account. But none of the other much more important functions of money are captured at all.

In particular, money does not serve as a medium of exchange. Prices that clear the market are found, then all the goods are magically redistributed in such a way that the value of the bundle each person receives is exactly equal to the value of the bundle they give up. In the real world, this would obviously be accomplished by carrying out all transactions with bits of paper we call money, where the number of pieces of paper required to buy a good is equal to its equilibrium price. This can happen because we have a society-wide agreement to treat the bits of paper as if they are valuable. This can never happen in general equilibrium theory - there is no room in the model for social constructs or government fiat. And in their absence, why would anyone accept useless bits of paper in exchange for real, intrinsically useful goods? This also implies the equilibrium price of money is zero, rendering it useless as a store of value or a standard of deferred payment. The result is that general equilibrium theory is really a theory of frictionless, money-free bartering. Which, you may have noticed, is somewhat lacking in realism.

No unemployment

In general equilibrium theory, market-clearing prices always prevail. Excess supply or demand is assumed away - it simply cannot happen. That is rather unfortunate because unemployment, perhaps the central quantity of interest in macroeconomic forecasting and policymaking, is a failure of labour markets to clear. In general equilibrium theory, unemployment simply does not exist.

No price-setting

In general equilibrium theory, no one sets prices. They are simply sent down as manna from heaven. Everyone calculates what bundle they would buy at every possible set of prices, and divine intervention selects a set of prices that clears the market. At no point does it occur to anyone that they might be able to influence prices.

No strategy

General equilibrium theory is not a game. Agents in the model behave as if choosing from a menu of options in complete isolation from everyone else. There is no notion that anyone else’s behaviour might affect your payoff. This is obviously completely at odds with the real world, where firms ruthlessly strategise against each other to maximise their profits.

These are just the failings of general equilibrium theory. However, standard macroeconomic models are in many ways even worse, because they make simplifying assumptions that even more thoroughly divorce the model from reality. In particular, they typically model the economy of an entire country as if it contains exactly one person, one firm, and a handful of goods that are traded. In case that didn’t strike you as obviously doomed to failure, there are theorems indicating you just can’t do this (see the Gorman aggregation theorem, the Cambridge capital controversy).

To summarise

Standard macroeconomic models that are routinely used by major financial institutions to model entire nations are typically based on frameworks that do not have money and operate through frictionless bartering, where there is no unemployment, sellers cannot choose what price they offer to sell at, there is no strategic considerations, there is precisely one consumer and one firm, and only a handful of goods are traded. And many economists seem to be pretty satisfied with this state of affairs.

Yes, I find it hard to believe too.

When I worked in economics, I was most certainly not happy with this state of affairs. I came up with an alternative framework that in principle fixes many or all of these problems. What I quickly discovered, though, is that for various reasons my work was virtually unpublishable in mainstream economics journals. That is, however, a story for another day.